Bullfrog Removal from the Glenwood Valley to the Columbia Gorge

By: Sienna Krulis, Adam Yawdoszyn, and Jack Fogarty

As night descends over the Mt. Adams region and the Columbia River Gorge, many animals retreat into their burrows seeking rest until dawn, but others rise in the darkness. Hungry and patient, their golden eyes breach the surface of quiet waters. Invasive American bullfrogs wait suspended, ready to lunge indiscriminately at any small sign of movement that crosses their path. Underneath the same moonlight, a different kind of hunter navigates through the water. Wading through the wetlands are a handful of trained technicians armed with high-powered headlamps. They are working to restore balance to the native ecosystems disrupted by this aquatic invader.

The American bullfrog is a destructive invasive species that was introduced to western watersheds starting in the late 1800s. Originally from eastern North America, bullfrogs are opportunistic predators that will eat anything that can fit into their jaws, including fish, invertebrates, birds, small rodents, bats, salamanders, turtles, snakes, and other frogs. Bullfrogs also grow much larger and reproduce at faster rates than any native frog species in the region, making them a leading cause of population decline for many West Coast species.

In partnership with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Mt. Adams Resource Stewards (MARS) introduced the Bullfrog Removal Action Team (BRAT) in 2020 to conserve, protect, and enhance the native population of Oregon spotted frogs found in the Glenwood Valley. The Oregon spotted frog is a federally threatened and state-endangered species facing significant declines across its native range. It is also the most aquatic frog species in the Pacific Northwest, playing a critical role in maintaining the Glenwood Valley ecosystem.

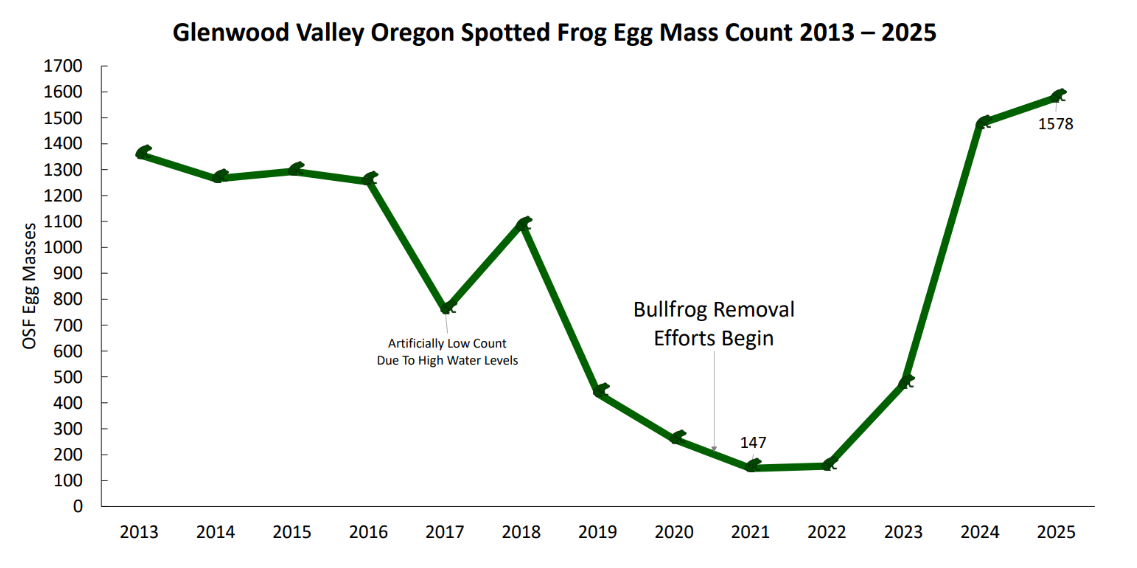

The BRAT crew, based at Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge (Conboy Lake NWR), addresses the largest targetable issue threatening Oregon spotted frogs by conducting systematic bullfrog removal. Since 2020, the crew has removed over 60,000 invasive frogs. And it’s working: annual Oregon spotted frog surveys show a tenfold increase in the native population since it reached its lowest point shortly after bullfrog removal efforts began. The success of the program is due largely to crewmembers’ deep understanding of frog behavior and biology, and to their commitment to the cause night after night.

Bullfrog Breeding Activity at Conboy Lake NWR

Bullfrog breeding season, typically late May to early August, is a race against time for the BRAT crew. Female bullfrogs can each lay an egg mass containing up to 20,000 eggs that hatch out within three days in average summer conditions, resulting in potentially hundreds or thousands of surviving frogs added to the ecosystem. Male bullfrogs traditionally congregate in large breeding groups called leks, where older males with the deepest and loudest calls maintain a centralized territory, leaving the younger males around the outskirts to either compete for their own territory or attempt to intercept breeding females as they make their way to the central breeding male. In his four seasons of bullfrog removal efforts at Conboy Lake NWR, BRAT program lead Adam Yawdoszyn has observed marked behavioral changes among breeding males:

From 2021 through 2024, we saw a distinct shift away from the more traditional lek breeding structure toward one that was more decentralized. Reduced population density likely made it simultaneously more difficult for male bullfrogs to congregate in numbers necessary for a traditional lek and more attractive for males to set up their own territories apart from competition and increased hunting pressure. However, in 2025, bullfrog breeding and male calling were considerably more concentrated. It seemed as if the bullfrogs had collectively decided that the spread-out approach to breeding was not working, and so instead they should do their best to congregate and attempt to recreate more traditional leks. Bullfrogs do not have the social intelligence required to make such a decision, so it’s likely an instinctual response, but it will be very interesting to see what sort of breeding behaviors are exhibited in future years.

“Every bullfrog breeding season provides its own challenges and reveals new behaviors.”

Oregon Spotted Frog Observations

While hunting bullfrogs at night, the BRAT crew records observational data for every Oregon spotted frog encountered in the field, including life stage estimation, GPS data, and, if possible, a photograph of their unique spot pattern. This information, aside from being valuable for population estimates, is used to track individual frog movements across the Glenwood Valley and will ideally help predict their seasonal movements in the future.

In 2025, the BRAT crew reported increased subadult spotted frog observations, indicating success from the recent spotted frog breeding seasons. In the fall, the crew also recorded more sightings of large adult spotted frogs that were seemingly preparing their clutches of eggs for the upcoming spring breeding season. These observations suggest that the spotted frog population will continue to increase next year and hopefully beyond.

“I’m so lucky to be able to see these endangered frogs in their native habitat and thriving...I have seen their numbers increase with my own eyes, and it is so wonderful to know that my efforts have helped their population grow.”

Bullfrog Removal in the Columbia River Gorge

Downstream from the Glenwood Valley, in hidden hillside wetlands and highway ponds along the Columbia River Gorge, is a longer-lived species engaged in a fight for survival: the Western pond turtle. Previously more widespread across Washington, this state-endangered species now clings to a few isolated pockets of habitat near the Puget Sound and along the Gorge. Western pond turtles can live anywhere from 50 to 70 years, but they face a critical life history challenge: young turtles only begin to reach reproductive age at around 10 years old. This long adolescent period exacerbates the impact of bullfrog predation on Western pond turtle recruitment, defined as the frequency of juvenile turtles joining the adult population.

Building upon the success of the BRAT crew at Conboy Lake NWR, MARS expanded the program in 2024 to include a second BRAT crew based in the Stevenson area. This new team significantly expands upon 30 years of previous bullfrog control efforts in critical pond turtle habitat, and involves partnership with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Friends of the Columbia Gorge, and Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area.

The Gorge BRAT crew showed proof of concept for their work by increasing turtle survivorship in an initial target area where they removed all adult bullfrogs, leading to a more stable juvenile pond turtle population unburdened by invasive predators. Following this success, in 2025, the Gorge BRAT team doubled in size from two to four technicians, allowing for more consistent and targeted removal efforts across a greater number of ponds.

Because pond turtles take over a decade to reach breeding age, their road to recovery will be slower than that of the Oregon spotted frogs at Conboy Lake NWR, but that is exactly why bullfrog removal in the Gorge is so critical. The efforts of today lay the groundwork for the survival of future generations of pond turtles. Gorge BRAT crew lead Jack Fogarty explains initial successes observed in the Gorge:

Turtles involved in the headstarting program at the Oregon Zoo, which aims to rear wild hatchlings in captivity until they’re too large for bullfrogs to eat, are marked for individual identification. In areas where long-term efforts have fully cleared out bullfrogs, there have been increasing sightings of small adult turtles which are not marked, indicating that they survived the gauntlet on their own. As we continue to remove the large adult frogs and mop up the juvenile frog population booms that appear in their wake, we are creating a long runway for future recovery of Western pond turtles.

Looking Forward

Bullfrog removal has proven to be a powerful control method that benefits declining native species by restoring ecosystems to a more natural state. After five years of concentrated bullfrog removal efforts at Conboy Lake NWR, native Oregon spotted frog populations have significantly rebounded. Techniques and experience gained at Conboy Lake NWR provide a foundation for similar removal efforts in the Gorge, where they offer a new hope for the long-term recovery of local Western pond turtle populations and potentially other declining species threatened by bullfrog invasion. We thank the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Friends of the Gorge, the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area, and additional partners for collaborating on these initiatives supporting local biodiversity now and into the future.

Click here to learn more about the BRAT crew, or reach out to:

Adam Yawdoszyn, BRAT Program Lead

adam@mtadamsstewards.org